6. Interactions between actors: mixed complementarity problems#

In this section we consider an approach to depict how relations between actors affect the outcome of the electricity markets which, in Section 5, we had considered as optimisation problems from the perspective of a market operator.

Before we move on to this consideration of different market participants as separate actors, it is first necessary to set a solid foundation. First, we will discuss some basic concepts in game theory, such as Pareto efficiency and Nash and Nash-Cournot games. Then, we will briefly describe the fundamentals of mixed complementarity before we discover their relevance to study energy markets.

6.1. Game theory basics#

So far, we have considered the dispatch of power from the system perspective, i.e, how would a central planner dispatch the available power plants in the most cost-efficient way. This assumes that this central planner has full control of and information on these power plants. Modern, liberalized electricity systems do not work in such a centralized manner, but are rather market-based, meaning that a large set of actors (e.g., producers, consumers) are involved. These actors act in a selfish manner to maximize their profits or utility.

To model the behaviour of different actors in the market, we can use a mix of optimisation and game theory. Let’s begin with one of the classic game theory examples, the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Assume that two suspected bank robbers, Thelma and Louise, are captured by the police. They are separated and have the choice of whether or not to confess and implicate the other:

if both confess, they both serve 10 years in jail;

if one confesses and implicates the other and the other doesn’t, she goes free, the other serves 20 years;

if none of them confess, they both serve 1 year.

The payoff matrix of the prisoner’s dilemma can be seen in Table 6.1. Based on the payoff matrix, the optimal scenario is for neither Thelma nor Louise to confess, as this leads to less years in prison in total. This situation of the payoff matrix (1,1) is the Pareto-optimal outcome of the prisoner’s dilemma.

On the contrary, the Nash equilibrium of the dilemma is when both Thelma and Louise confess, and each serves 10 years in prison. The presented example is a case of a “non-cooperative game” where Thelma and Louise selfishly try to maximize their own utility \(Π_α\) by selecting a strategy \(χ_α\). In such a non-cooperative game, each agent selects its strategy simultaneously and independently, assuming that the strategy of the other players \(χ_{-α}\) is given. In a state of Nash equilibrium (denoted with \(*\)) none of the players has an incentive to deviate from the equilibrium strategy \(χ_α^*\) as no alternative feasible strategy \(χ_α \in Φ_α\) exists that leads to more utility. Formally, the Nash equilibrium condition reads:

Thelma confesses |

Thelma does not confess |

|

|---|---|---|

Louise confesses |

(10, 10) |

(20, 0) |

Louise does not confess |

(0, 20) |

(1, 1) |

Linking this back to our example, the case where both Thelma and Louise confess is the Nash equilibrium point since Thelma has no utility if she changes her strategy unilaterally. If she chooses to not confess, instead of 10 years in prison, she will receive 20 years while Thelma will be released. In other terms, her utility will be lower than the Nash-equilibrium point. In summary, in Nash games, each actor chooses the strategy with the highest payoff for themselves, assuming that the other actors have done the same at the same time [].

Such Nash games can be used to describe perfectly competitive electricity markets, where the producers and consumers are price-takers. This means that the market actors do not anticipate how their own actions will influence the market price. In contrast, in Nash-Cournot games, each firm anticipates its impact on the market through the knowledge of the inversion function []. More specifically, in a Nash-Cournot game, the firms compete on production quantity and anticipate the impact of their own actions on the commodity price.

Pareto optimal outcome

The Pareto optimal strategy, named after the economist Vilfredo Pareto, corresponds to the strategy where no alternative strategy exists that would benefit any of the actors. Every actor is as well off as they can be: it is the optimal solution for all actors jointly.

We will study electricity market situations as Nash and Nash-Cournot games. These games can be represented as a set of optimisation problems (describing the decision problems of each of the involved actors) that are linked together via a common coupling constraint (typically the market clearing constraint, i.e. the demand-supply balance constraint). We can then formulate a “mixed complementarity problem” (MCP) which is associated to these linked optimisation problems. The MCP is given by the set of KKT conditions of the decision problems of the involved agents and the coupling constraint. Before we continue, let’s briefly revisit the KKT conditions.

6.2. From KKT conditions to mixed complementarity problems (MCPs)#

Let’s assume a general optimisation problem, as seen below :

The Lagrangian reads :

The KKT conditions of the problem are the following :

For linear and convex quadratic optimisation problems, the KKT conditions are both sufficient and necessary conditions for optimality. In other words, any solution that satisfies these conditions is guaranteed to be an optimal solution to the optimisation problem. This system of equations is an example of a mixed complementarity problem (see box below). In the following paragraphs, we will examine how mixed complementarity problems (MCP) can help us solve market clearing problems from the perspective of market actors.

What is a mixed complementarity problem (MCP)?

The KKT conditions introduced in Section 4.2 are a special case of a mixed complementarity problem (MCP). Below, we will use our existing knowledge of KKT conditions to formulate such problems - including by combining the KKT conditions from more than one optimisation problem into a single MCP.

You can find an extensive introduction to complementarity problems more generally, including formal mathematical definitions, and many applications to energy (markets), in [].

6.3. Nash games#

We will first study a simple, single-time step market clearing problem. We start with the perspective of the market clearing operator, leveraging our knowledge of optimisation and electricity markets. Next, we move to the perspective of the individual market participants, assuming they compete in a Nash game. Based on the KKT conditions of both problems, we will be able to show that both formulations yield the same result. We conclude this section by introducing an alternative, condensed formulation using inverse demand functions, which prepares us for the Nash-Cournot games in the following section.

6.3.1. The market clearing problem from the perspective of the market operator#

Let’s start with a simple market clearing problem. The market-clearing problem is relevant to a pool-like market. We start by formulating the market clearing problem from the perspective of the market operator, which aims at maximizing social welfare. The optimisation problem is considered under given price-quantity pairs of supply and demand agents, \((P_i^s, Q_i^s), (P_j^d, Q_j^d)\). This is exactly the same problem that we formulated with “bids” and “offers” in Section 5.4, just with different notation. This optimisation problem can be formulated as :

This market clearing problem allows for determining the demand served \(q^d_j\) and supply cleared \(q^s_i\) in the market. The market clearing price \(\lambda\) is the dual variable associated with the supply-demand balance.

The KKT conditions of the market-clearing problem in Eq. (6.3) are :

6.3.2. The market clearing problem from the perspective of the market participants and the resulting MCP#

Now let’s look at the issue from the perspective of the supply and demand agents participating in the electricity market. Contrary to what is presented up to now, supply and demand agents now have to decide on how much to generate or consume. So what is the optimisation problem faced by the suppliers (generators) and the demand agents (customers, retailers) that aim to maximize their profit or utility?

First, the generators want to maximize their profit considering the market clearing price as given (recall that in Nash games, agents are assumed to be price-takers). In that case, the market clearing price \(λ\) is a parameter and not a decision variable in the optimisation problem of the individual market participants. Note that it will be a decision variable in the MCP describing the Nash game.

The optimisation problem of each agents \(i\) in Eq. (6.5) reads:

where :

The KKT conditions of the problem in Eq. (6.5) are the following :

Secondly, the demand agents aim to maximize their utility, again by using the assumption that their actions do not influence the market price. Therefore, the optimisation problem faced by the demand-side agents is :

where :

The KKT conditions of the problem in Eq. (6.7) are :

The two different optimisation problems are connected through a common linking or coupling constraint, requiring supply and demand quantities to match. That is Eq. (2) of the initial market clearing problem. To determine the equilibrium of the Nash game between demand and supply agents, we need to simultaneously solve the supply-side problems (6.5), the demand-side problems (6.7) and the linking constraint (2) of Problem (6.3).

By concatenating the KKTs of the individual problems (Eqs. (6.5), (6.7)) along with the linking constraint, we obtain the mixed complementarity problem associated with this Nash game:

6.3.3. Solving MCPs#

There are several ways to determine the equilibrium in this game. We can follow one of the three methods :

This MCP can be solved directly either with dedicated solvers such as PATH or as a feasibility problem (NLP or MILP) using optimisation. In simple cases, you can determine the equilibrium solution analytically by deriving best response functions (see Section 6.4). Larger problems, however, are very challenging to solve directly as we are - by definition, due to the complementarity conditions - dealing with non-linear problems.

Apply price-search algorithms and iterative methods. The general principle of such methods is as follows: we start by making an educated guess on what the equilibrium price \(\lambda\) in the game is. We present this price to each of the agents in the game and solve their decision problems. Those solutions are optimal from their perspective, but may not ensure that demand and supply are matched (Eq. (2)). Based on the mismatch in demand and supply, we adjust the price \(\lambda\) accordingly and repeat this process until we have found the equilibrium price \(\lambda\). We will not cover these techniques here.

For some MCPs, we can derive an equivalent optimisation problem (EOP) and solve it like we do other problems - using mathematical programming languages such as YALMIP or Pyomo and solvers such as Gurobi. This builds on the notion that if we can find an optimisation problem that is described by the same set of KKT conditions as the MCP, solutions to that optimisation problem will – by definition – also be solutions to the MCP.

Comparing the KKTs of the concatenated problem in Eq. (6.4) with those of the market-clearing problem in Eq. (6.3), we can deduce that there is a difference in the following constraints :

However, we know that in competitive electricity markets generators bid their capacity at variable cost and demand agents at their willingness to pay. Any other bid or offer would potentially lead to foregone profits (e.g., offering above variable cost may result in a generator not being cleared while it could have been operating profitably) or loss-making market outcomes (e.g., offering below variable cost may result in running at prices below variable cost, resulting in a loss).

Hence, we can conclude \(VC_i = P^s_i\) and \(WTP_j = P^d_j\). Therefore, constraint (10a) is equal to constraint (5b) and (13a) to (5a). Through this observation, we can conclude that the KKTs of the MCP are the same as those of the market-clearing problem. The main implication of this is that a solution that satisfies the KKTs of the market-clearing problem will also be a solution of the MCP. In summary, we have shown that the market-clearing problem is the equivalent optimization problem (EOP) of the MCP.

Warning

Every optimisation has an equivalent MCP, but not every MCP has an equivalent optimisation problem.

6.3.4. An alternative formulation of the Nash game#

Another formulation of the Nash game above can be presented through the use of an inverse demand function. We use a linear relationship between the price of electricity and the demanded quantity to represent the demand side of the market. The linear equation takes the form of :

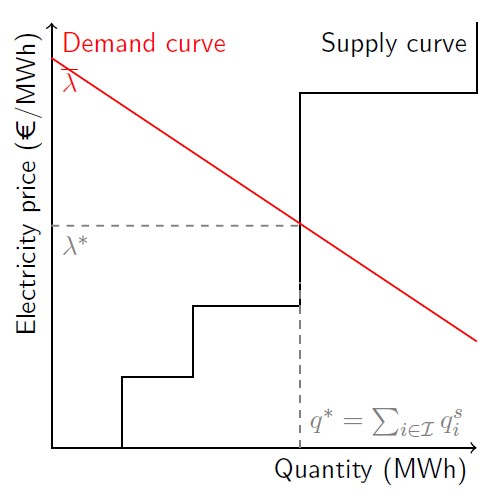

Using the market clearing constraint, we know \(\sum_{j \in J} q^d_j = \sum_{i \in I} q^s_i\), hence the inverse demand function can be rewritten as \(λ = \overline{λ} - β \cdot \sum_{i \in I} q^s_i\). In this way, we have eliminated the second vector of decision variables \(q^d_j\). The \(\overline{λ}\) is the interceptor of the demand curve and signifies the maximum willingness to pay and you can see the graphic interpretation of the inverse curve in Fig. 6.1. Taking all the above into account, the game can be finally reformulated as :

Fig. 6.1 Inverse demand function and supply curve, based on supply-side bid pairs.#

The KKT conditions of the decision problems of the suppliers and the inverse demand function jointly make up the MCP of this Nash game. Note that the inverse demand function participates as-is in the MCP, but is not part of the optimisation problem (it is outside of the curly brackets). That is the case since we are studying a Nash game, and therefore, the suppliers do not consider the impact of their actions on the price.

With the MCP defined, we can now derive the Equivalent Optimization problem to determine the equilibrium solution to the game in Eq. (6.12). Remember here, that the KKT conditions of the EOP have to match the MCP in order for the EOP to provide a solution to the initial problem. To derive the EOP, we make use of the graphical interpretation of the problem show in Fig. 6.1.

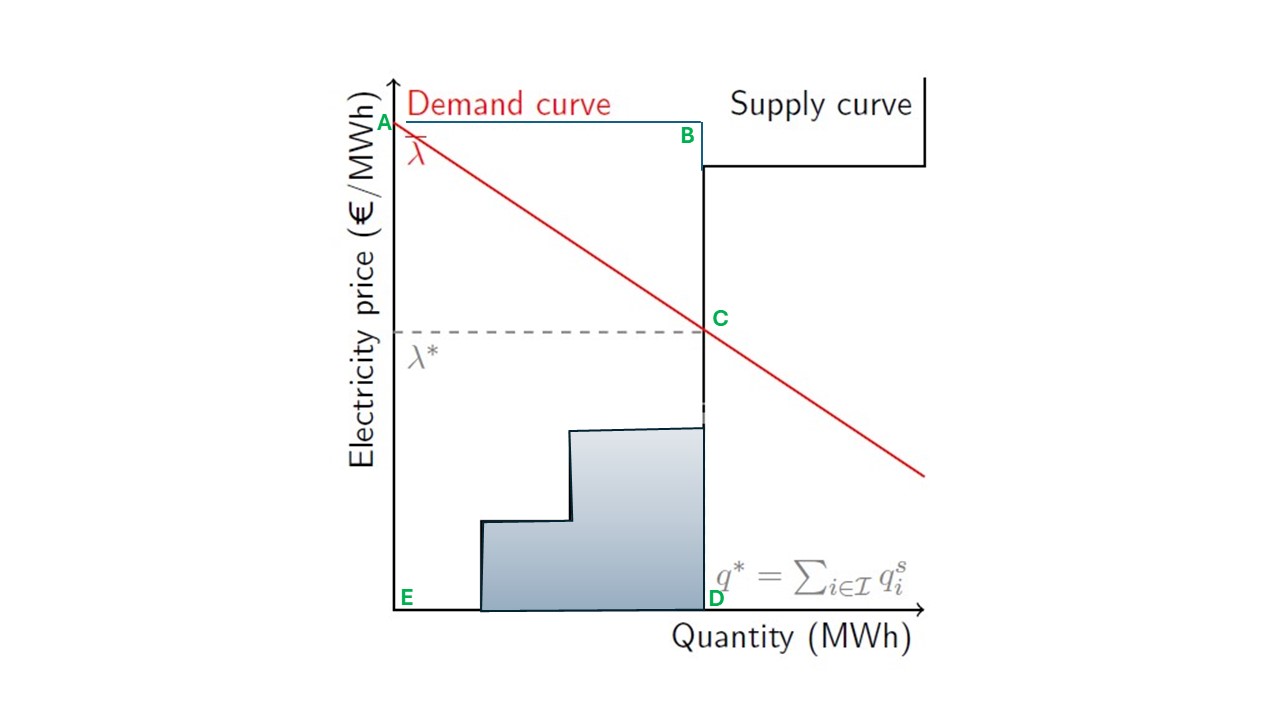

From the discussion above, we know that the Nash game between suppliers and consumers in perfectly competitive electricity markets will maximize social welfare in that market. Hence, we can formulate a candidate EOP which aims to maximize social welfare. Based on Fig. 6.2 and the fact that social welfare is the area between the demand and supply curve, social welfare can be computed as :

Fig. 6.2 Areas to calculate social welfare from inverse demand and supply curves.#

The EOP should furthermore consider the constraints of the suppliers, resulting in the following optimisation problem:

The equivalence of the MCP with the EOP can be demonstrated through the derivation of the KKTs for the EOP in Eq. (6.14). Note that we now have an optimisation problem with quadratic terms in the objective. However, these problems are still convex, hence, KKT conditions are – in all the cases that we consider – necessary and sufficient conditions for optimality. This also means that we can use solver software that supports solving quadratic problems, like Gurobi and Cplex, to efficiently obtain solutions.

6.4. Nash-Cournot games#

Up to now, we have assumed a perfectly competitive market, meaning firms have zero market power and act as pure price-takers. In Nash-Cournot games, we abandon these assumptions and allow agents to strategically anticipate how their own quantity decisions influence the price (and hence their profit or utility). Each agent takes the decisions of the other players as given, as in a Nash game.

6.4.1. A simple Nash-Cournot game#

To simplify notation, we will make use of an inverse demand curve to simulate the demand side. To allow agents to strategically anticipate how their actions influence the price, the inverse demand curve (14, below) now is part of the optimisation problem (note the position of the curly bracket). The Nash-Cournot game is:

The MCP associated with the Nash-Cournot game in Eq. (6.15) can be obtained by deriving the KKT conditions of the optimisation problems that make up the game:

To understand the derivation of (10a’) in Eq. (6.16), we can say that the Lagrangian of (6.15) is:

Substituting equation (14) from Eq. (6.15), which defines the inverse demand function, into the Lagrangian, yields:

Finally, differentiating the Lagrangian with respect to \(q^s_i\) yields (10a’) in (6.16):

6.4.2. Obtaining Nash-Cournot Equilibria via equivalent optimization problems#

Nash-Cournot games can be solved with similar methods to Nash games, by either:

directly solving the MCP: analytically/graphically using best response functions or via dedicated solvers;

through iterative price search algorithms;

through the derivation of an equivalent optimization problem, which can be solved through optimisation algorithms.

How can the EOP be obtained in the case of a Nash-Cournot game? As always, this entails finding an optimisation problem that has the same KKT conditions as the MCP (6.16). In contrast to the Nash game, we cannot leverage any knowledge related to the equilibrium solution: Nash-Cournot equilibria are not welfare-maximizing. Comparing the MCP of the Nash game and the Nash-Cournot game, however, shows that they are identical with the exception of Eq. (10a) and Eq. (10a’).

The optimality condition in the Nash-Cournot game has an extra term of the form \(β \cdot q^s_i\). With this information, we can now adjust the objective of EOP of the Nash game to ensure this additional term shows up in the KKT conditions. We do this by integrating the term that differentiates Eq. (10a) and Eq. (10a’) and adding it to the objective of the EOP of the Nash game.

The resulting EOP for the Nash-Cournot game with \(i \in I\) participants reads:

Note that the objective function of this EOP is no longer a measure of social welfare, in contrast to the objective of the EOP of the Nash game. The problem contains quadratic terms in the objective but is still convex.

6.5. Final remarks#

With the introduction of the mixed complementarity problems as a way to solve the Nash and Nash-Cournot games, we have introduced a paradigm shift in the way we study interactions between self-interested market participants. Up to now, we were considering the market only from the side of a central market operator that aims to clear the market. Now, with the techniques introduced in this section, we can study simple electricity markets as the interaction between different market actors. Specifically, through the Nash games, we can understand the participation of agents in a perfectly competitive market. To study how strategic behaviour and market power change market outcomes, we introduced the Nash-Cournot equilibrium.

For both Nash and Nash-Cournot games, we developed formulations of the game (i.e., the set of interrelated optimisation problems and the coupling constraint) and the corresponding mixed complementarity problem (i.e., the KKT conditions of the decision problems of the involved actors and the coupling constraint). We discussed how we can determine the equilibria in such games, focusing on equivalent optimization problems. For the Nash game, we showed that the equivalent optimization problem is a maximization of social welfare. We also obtained an equivalent optimization problem for the Nash-Cournot game.

These games allow making relationships and interactions between market agents explicit. In complex cases, for which the formulation of an optimisation problem is non-trivial, MCPs offer a more intuitive way of formalizing problems.